"The water came up to here," he points to the middle of his chest, nodding emphatically. "Two walls fell and the house filled up and fell down. The water took all the firewood and the clothes. It was scary, we had to go stay in the school up there," he tells us with eyes wide, pointing in the direction away from the coast.

Selvin Josue Arita and Samuel Mueve are both 8 years old. We chat with them in the yard, which is littered with tree trunks, barbed wire, posts, and trash, in between sections of deep mud. It’s June 3, 2010, three days after the tropical storm Agatha passed through El Salvador. The heavy rains that Agatha brought left much of the country impacted and coastal regions devastated.

Selvin and Samuel live in a small village called La Hachadura, on the southwestern border of El Salvador and Guatemala. Local people make a living from fishing and farming, growing beans, rice, coconuts, bananas, sugar cane and, in the highlands, coffee.

We pass from the yard where we were talking with Selvin and Samuel to introduce ourselves to the adults inside the house. Wet clothing is draped everywhere – on the roof, on what remains of the fencing, on logs and stumps – along with mattresses and any other object that can dry in the sun.

Margot Rivas greets us as we arrive at the house, and invites us in. Her husband pulls up some plastic chairs for us to sit in, and she returns to the kitchen area where she is making tortillas. A soup is cooking over coals to her left, and the small kitchen area is filled with smoke.

She has always lived in the zone, and it has always flooded, but that doesn’t make what just happened any easier. “The water came, but we didn’t want to leave our home and our animals. Someone came to warn us, but we didn’t want to leave everything behind.” Many people want to stay on their properties to try to keep the river from taking everything they have.

“In 1982 we lived a little lower, closer to the river, and one storm took everything with it. We moved up a little bit, to this house we are in now, but this time (with Agatha) it was almost the same. The river has always flooded, there was Hurricane Mitch, Hurricane Stan, but this time it was different,” she adds.

In the end, Margot and her family did move to higher land during the storm, despite their fears of losing everything. They, along with most other residents in the area, sought shelter in nearby schools until the storm and the flooding died down, then returned to see the damage. Bit by bit, the families began to put their lives back together. It was in this fragile period that we had gone to talk to the local people.

Highlands and lowlands

Progressio development worker Marcos Cerra Becerra has spent more than two years working in the municipality of San Francisco Menéndez. He’s a geographer from Spain, and came to work with Progressio partner Unidad Ecológica Salvadoreña, UNES, to support a land planning process in partnership with the mayor’s office.

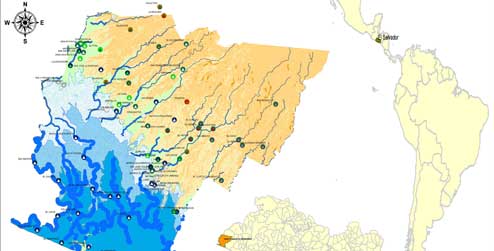

Marcos explained to me that the municipality is clearly divided into two parts: the highlands and the lowlands. “The highlands are mountainous, with rocks and cliffs, and the lowlands are very flat, less than 50 metres above sea level.

“Because the lowlands are flat and all the rivers and streams from the highlands flow through it, the lowlands are at extreme risk of flooding. Not only that, but the lowlands have been extremely deforested in order to create farmlands, which intensifies flooding. In the highlands, because it is mountainous and has cliffs, the principal risks are landslides and high winds.”

Climate change has become a hot topic in development work. Sometimes it’s used as a quick diagnosis to slap onto complex situations where several factors are at play. These can often be topography, environmental degradation, poverty, social and political inequality, and neoliberal economic practices which come together to create conditions of extreme vulnerability.

Marcos suggests that it’s misleading to attribute all of what happens in San Francisco Menéndez all to climate change. People throughout El Salvador live in conditions of vulnerability. This vulnerability is sometimes caused by climate change and sometimes not. But, climate change can make this vulnerability worse, and definitely doesn't help to make the situation any simpler.

Water

Victor Urbina dips the bucket, which is tied to a thin rope, down into the well. The white bucket clatters down, banging against the cement walls of the well until we hear a splash as it hits the water. He jerks the bucket back and forth, pulling the rope up in sections to show us the water he has pulled from the well.

“The water smells bad and is yellow, and we know we can’t drink it. We will get sick if we do. Sometimes even trash comes up in the well. No one has good water here. We all have the same problem with the wells.”

Victor lives in El Castaño, one of the coastal communities in the area. He is a fisherman. He and his various community members describe that when they drill a new well, fresh water can only be extracted from the well for a short period of time, until it turns increasingly salty and makes them sick.

It’s hard to get decent water for lots of reasons: the rivers are seasonal (they swell and flood in the rainy season and dry up in the dry season), extraction from wells reduces the amount of fresh water underground to use later, and deforestation impacts a water table that is already fragile. Added to that, large-scale agriculture and cattle farming need very large amounts of water, leaving little left over for subsistence farming and household consumption.

Vulnerability

If this area is susceptible to so many risks, why do people choose to live here? The truth is the majority of Salvadorans live in extreme risk of one kind of another.

According to the The United Nations Disaster Assessment and Coordination (UNDAC) team in a 2010 report, about 90% of the territory and 95% of the people in El Salvador are highly vulnerable to natural disasters like hurricanes, tropical storms, flooding, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and droughts. All of this is made worse by poverty and the political, social, and economic realities of a post-war society.

No-one knows what the impacts of climate change will be, but we can be pretty sure that it won’t be good. For this reason, organisations like UNES work to advocate for just and sustainable environmental practices at a political level, but also to implement processes that begin to address the complexity in San Francisco Menéndez.

Working for adaptation

I asked Marcos to explain what his work in Land Planning in the zone is, and how it is related to all the risks there.

"The land planning work in the area, although really it’s technical, we could say that idea is political. In El Salvador, the state is very centralized. The central government doesn’t have capacity to decide what happens with the land. And anyway the principle of private property comes before anything else, allowing people to build what they want where they want and how they want, taking precedence before environmental protection laws."

Land planning is essentially a development plan that takes into account the ecosystems, territory, animals, people (and their livelihoods) in the area, and tries to find most harmonious and environmentally sustainable way for it to all fit together. This is useful to both prevent people from living in high risk zones, but also to prevent businesses or large land owners from engaging in activities (deforestation, soil erosion, dominating water sources) that create even higher risks.

The first step of developing the land plan in San Francisco Menéndez was to conduct a diagnosis with the communities and mayor's office in the zone, to identify what the principal features of the land are according to its residents. Then came the creation of maps to include all of these elements, and finally writing a document that outlines recommendations for the plan.

The law has been in discussion during all of Marcos' entire time as a DW. As Marcos comments, "As soon as there is a big storm that causes damage, all the assembly people talk about the necessity to pass the law, but then life goes back to normal and nothing advances."

This is mostly because a law like this would mean challenging traditional power structures, where the economic oligarchy, who are usually the people who own the companies that want to build wherever they like. Nevertheless, UNES and other allies are continuing to advocate for the law, and actually include it in their recommendations and advocacy around climate change and adaptation in El Salvador.

A lot remains unknown

We don't know exactly what impacts climate change is having or will have in San Francisco Menéndez. It brings a whole new element of "ifs" and "buts" into the equation.

Things vary in the area, some to do with climate change. There is a lot that is unknown. But what we do know is that it is difficult to recuperate the delicate balance of fresh and salt water that the mangroves and wetlands depend on, and that it is difficult to create conditions that are more favorable for regenerating the fish and animals that are diminishing in the area.

We also know that these ecosystems are not being cared for, and that the majority of the population depends on them for their survival. We know that El Salvador and many other poor countries are facing a water crisis. And we know that certain countries are more responsible for greenhouse gas emissions, the principal cause of climate change, than other.

The resilience of the population of the coastal area of San Francisco Menéndez is unquestionable. Tools like land planning help overcome the complicated tangle of factors, and give hope for the future of these communities and so many more who just happen to live in a beautiful, if vulnerable, part of the world.

Maggie Von Vogt is a Progressio development worker at UNES in El Salvador. Maggie will be accompanying Progressio partners to the UN climate talks in Cancun this month so that the voices of local communities affected by climate change will be heard.

Photos: Dora Alicia de Arita, from San Francisco Menéndez, after the tropical storm Agatha, June 2010. Rodrigo Sura/ Diario CoLatino; Damage to a recently constructed $8 million road in San Francisco Menéndez due to flooding during Agatha, June 2010. Rodrigo Sura/ Diario CoLatino; Progressio development worker Marcos Cerra in a workshop for the development of the Participatory Territorial Diagnosis for the Sustainable Land Plan in San Francisco Menéndez, El Salvador. UNES/ Progressio; A map of the San Francisco Menéndez region in El Salvador, by Marcos Cerra Becerra. UNES/ Progressio.