In the UK, we throw away the equivalent of our body weight in waste every seven weeks. That means as a nation we produce enough rubbish to fill up the Albert Hall in two hours. (Source: C. B. Environmental Ltd.) We consume more and more and don’t really think about where our waste goes afterwards. We put it in the bin and then some kind people take it away, far, far from us, put it in landfills, condense it and cover it. Out of sight out of mind.

The picture couldn’t be more different in rural Zimbabwe. Rubbish is around us, it is part of life, it is in our face as a constant reminder that we need some radical changes in the way we produce, consume and dispose of our everyday products.

Of course people create less rubbish here than in the UK. Most people grow their own vegetables, and you can often buy food from local producers, delivered to your doorstep in a basket. No bags, no packaging. Lots of household waste tends to get a second life as well. Leftovers are eaten by animals, sometimes even composted, jars and tubs are reused for storage, and people even melt plastic into a floor polishing liquid. But it’s not all rosy either. Zimbabwe is developing fast, and that means that people consume more and produce more, and industrialised production means packaging, synthetic materials and of course waste. And while production tends to grow naturally in a developing country, waste management requires a more conscious effort.

With no waste collection available in rural areas, all household rubbish goes in a shallow hole in the ground and is set on fire. This means never ending open fires around the local villages, burning everything from food scraps to broken shoes, which not only poses a serious fire risk in such a hot and dry country, but the emission of unfiltered smoke and toxins also causes localised and general air pollution. This damages the ozone layer and contributes to health issues such as heart disease, various cancers, and damage to the nervous system, human development and reproductive health. (Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency).

But burning is still safer than not burning. The heat kills bacteria and helps people get rid of possible life threatening diseases. Where people live so near the rubbish, and food and water borne diseases are so prevalent, burning seems like the safest way of disposing of waste.

Our work in Nyanga is about supporting economic and community development in the most breath-taking area of the country, just on the border of the Nyangani National Park. As soon as we arrived we knew that we had to make sure that the work we do encourages an environmentally sustainable development, which respects and cherishes this beautiful land, so that it remains a resource for development for generations to come.

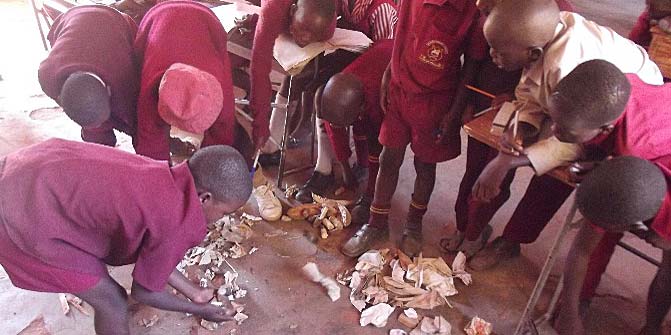

And while any major waste management or recycling project would have been out of the scope of our placement, we could still have a great impact by focusing on reducing the amount of waste that ends up in the pits to be burnt. We decided to incorporate waste management and recycling sessions in the programme we delivered to local primary school children. We wanted to make sure that the older generation’s resourcefulness and intuitive inclination towards reuse isn’t lost among children who are more and more exposed to the values of our disposable culture. And the children did what children do best. They took our challenge with great enthusiasm, collected all the rubbish they could find within a matter of minutes and with only a bit of encouragement they came up with some great ideas about repairing and reusing their newly found treasure – old mugs can be washed and reused, paper should be written on both sides and then it can be used for starting a fire, old clothes can be given away to those who are less fortunate.

We also asked for children’s help with a little problem of our own. As the drinking water in Nyanga is not safe to consume untreated, we have been given a seemingly endless supply of bottled water by Progressio to last throughout our placement. 18 cases per person, 12 bottles per case. With ten people in our group that adds up to 1,080 litres of clear water and 2,160 plastic bottles (!!). There was no way we could have burnt all these with a clear conscience, so we had to come up with some solutions for putting them to good use. The children were great again. They helped us transform some of our bottles into planters for seedlings, which will then be grown and sold by the students to raise money for the school. More bottles have been given to local nurseries for making toys and learning materials. Some of our bottles will become instruments, so that the little ones will be heard by making a lot of happy noise. Lots of empty bottles have been given out to school children who will use them as water bottles for treated water.

Additionally, we used some of our bottles as prompts for encouraging discussions about creativity and income generating activities. We asked local rural women’s assemblies and HIV support groups to come up with ideas about how to use bottles for generating income, and once again we were amazed by the local people’s ability to see opportunities where we only saw rubbish. Ideas flew and some of our bottles will soon be used for re-selling oil and paraffin purchased in bulk, and even preserving tomatoes.

Let these children’s and women’s resourcefulness be a message for all of us on World Environment Day, so that next time maybe we too can see the value in the “waste” around us, and become inspired to buy less, reuse more and take better care of our planet for the sake of us all.

Written by ICS volunteer Eszter Tarcsafalvi. Photos by Sebastian Scott and Eszter Tarcsafalvi.