Lima, the capital of Peru, is the second largest city in the world located in a desert, after Cairo in Egypt. Yet the Rímac, Chillón and Lurín rivers, which form the main water source for Lima, have an average water volume of just one percent of the water in the Nile.

So it will be no surprise to learn that this rapidly-growing city of 9 million people faces a severe water crisis, particularly in the face of the effects of climate change, severe contamination, and above all, highly inefficient water management with a lot of water loss because of inadequate infrastructure and lack of awareness about water conservation.

But when you ask people what their promises and hopes are for the rivers and watersheds of Lima, they have a different vision:

- ‘I would like a river full of life! We can achieve it – nothing is too difficult. Let’s help our planet!’

- ‘I promise not to unnecessarily waste water.’

- ‘I promise not to leave the tap on and to encourage others to save water.’

- ‘Please would the authorities put more effort into cleaning the Rimac and other rivers.’

- ‘I would like to see animals in the river, and birds and stones so that the river is healthy and we care for our environment.’

- ‘I would like the River Rimac to be beautiful.’

These comments were submitted as part of awareness-raising activities for children, young people and adults run by Aquafondo, the organisation that I work with. The key concerns were to protect the natural and cultural diversity in the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín watersheds and the importance of conserving water. So how can this be achieved?

The three small rivers which provide water to Lima originate at an altitude of about 4500 meters above sea level. (Pictured above is Ticticocha lake, where the Rímac river originates; below is the Santa Eulalia river, one of the main tributaries of the Rímac.)

During the whole of their course through the mountains towards Lima, their waters are used by smallholder farmers, villages, mining companies, industries, hydroelectric plants, and in the end, by almost 9 million domestic water users in Lima. Each of these uses at the same time generates water pollution; in the lower parts of the catchments pollution with urban waste is severe.

Until now in Peru, one of the most important groups of water users, the rural communities, has been largely excluded from decision making about water management. The government and a small number of private powerful water users have always been the ones managing this important resource, ignoring the interests and traditional ways of water management of the smallholder farmers. Luckily, with the approval of a new national Water Law, things have now started to change slowly.

The new water law promotes an integral and participative approach and defines that every group of river catchment areas should set up a ‘catchment council’, uniting the relevant authorities and industrial, domestic, and agricultural water users, including native and rural communities. Together, these stakeholders will have to write a management plan for their catchment areas, representing the views and interests of every group. This plan will be legally binding and is therefore a very important mechanism for water users to have their voices heard.

In Lima, Aquafondo, which is a private sector/NGO partnership set up to improve water management, has assumed the challenge of organising the Catchment Council in close collaboration with the regional governments and the Nation Water Authority. Not an easy task, considering the size of the intervention area (over 8000 square kilometers!) and the number of stakeholders involved: over 70 local governments, more than 80 rural communities, a high number of powerful mining and industrial companies, and 9 million domestic water users in the lower part of the watersheds.

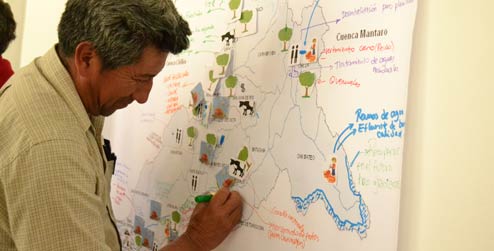

A first step in setting up the catchment council is informing people about the new law and the forming of the Catchment Councils, and getting to know their opinion and vision about water management. Aquafondo has organised 15 decentralised workshops, inviting all stakeholder groups, especially making sure the smallholder farmers were well represented. (Pictured above are participants at one of the workshops; below, creating a common vision for the watershed using participatory mapping.)

For many farmers this was the first time they were consulted about their needs and opinions in water related issues in the presence of the government and private companies, with which they often have conflicts about water use and contamination. The next step will be the election of the members of the council, which will be carried out the coming months.

Aquafondo will be closely involved in the elections, making sure it is done in a transparent and fair way. And once the council has been established, Aquafondo will be strengthening and advising this important institution, ensuring that the intention of the water law – to create an integral and participative water management system – is put into practice in Lima. Hopefully this example will be replicated in other parts of the country.

Sonja Bleeker is a Progressio development worker with Aquafondo in Peru.

Find out more about the work of Aquafondo in their June 2012 information bulletin (in Spanish) which includes:

- Information about the catchment council workshops that have taken place

- The creation of a new financing mechanism, Forasan, which will generate funds to be invested in water resource management and care (much like Aquafondo)

- The need to involve traditional Andean knowledge about water management in modern schemes

- Aquafondo’s involvement in an environmental fair in Lima to coincide with international environment day

Download the Aquafondo information bulletin (4.3MB PDF) in Spanish

Photo at top: a smallholder farmer in the upper part of the Rímac watershed.