The existence of indigenous people in El Salvador in the 21st century is a largely over-looked issue. In academic studies, they are almost exclusively referred to in the past tense. This is because the persecution of indigenous people in EL Salvador has been continuing since the 16th century. Despite a ten-year struggle against the conquistadores by the Pipil people, the Spaniards claimed victory over the territory in 1528. This set off a chain of events in El Salvadorian history, which has largely led to acculturation of indigenous peoples.

Unlike neighbouring Honduras, with mountainous areas where Indian populations (a mix of Olmec, late Mayan descendants, Lenca, Pipil, Chorti and Pok’omama) could isolate themselves from the invaders, El Salvadorians were thrown together with the Spaniards from the beginning. Some northern territories, especially in mountainous areas, were largely untouched, and communities were allowed to continue their native traditional practices. The cocoa and indigo farms were places of indentured labour however, where the native population was forced to work alongside imported African slaves. The working conditions were appalling and many workers died. Despite efforts by indigenous groups, the land-owning elite retained power and uprisings were met with severe repression.

On 15 September 1821, El Salvador was granted freedom from Spain. At this point, most indigenous peoples spoke only Spanish, as fear of reprisals forced them to abandon traditional lands, customs, dress and language. This was initially celebrated as the new constitution prohibited forced labour. However, many indigenous people were left poor, landless and disgruntled as a handful of families retained ownership over most of the land.

During the time where EL Salvador withdrew from the Federation of Central America that it initially entered into with Mexico, indigo was reduced in value due to its synthetic counterparts and coffee became the main export (90 per cent of the total exports) by the beginning of the 20th century. This was made possible by the newly instated government reclaiming mountainous land under the pretense that it prevented wide-spread economic growth. As a result, the last true isolated strongholds of native peoples in the mountains were removed and placed into government hands. Despite various efforts in the 19th and early 20th century to redress the economic imbalances between the land-owning elite and the indigenous poor, there had been very little progress and 95 per cent of wealth from coffee exports was controlled by 2 per cent of the population.

Due to the Wall Street crash in the United States of America in 1929, the value of coffee plummeted. In January 1932, fueled by terrible working conditions for the poor indigenous as well as an ingrained inability to support themselves as subsidence crops had largely been removed to make way for cash crops, Augustín Farabundo Martí, a founder of the Central American Socialist Party, led an uprising of peasants and indigenous people. The uprising sacked the Sonsonate area randomly over a period of 72 hours with thousands of people armed with machetes. 35 ladinos were killed - non-indigenous peoples.

The military reprisals, known as ‘La Matanza’ were a systematic murder of indigenous-looking people. They were extremely thorough and women and children were not spared; between 35,000 and 50,000 people were killed. More than ever, those who identified as native peoples adopted the Spanish language and Catholic religion, abandoning native dress in order to protect their families from a rampant racism that pervaded the country throughout the first half of the 20th century. This process accelerated during the 1980-1992 civil war, when death squads killed thousands. That further affected indigenous people who, as part of the marginalised rural poor, were sometimes associated with targeted grassroots organisations. The Peace Accords of 1992 failed to address the rights of native peoples and all human-rights abuses were forgiven once peace was declared, so there was seen to be very little justice for indigenous people.

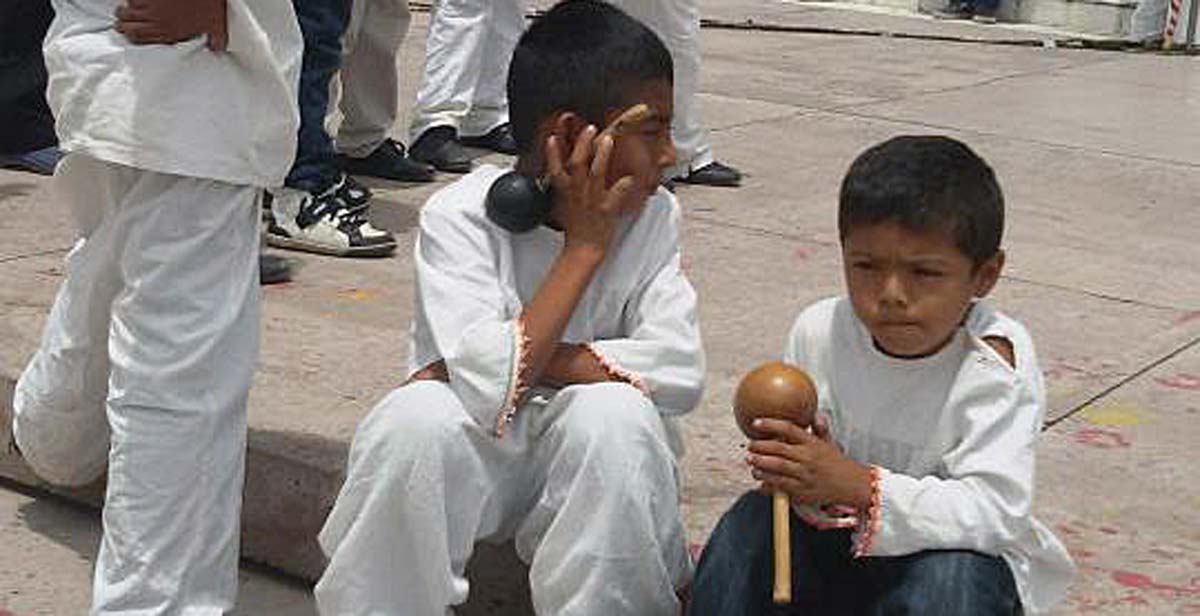

Until 2014, this issue had been largely unaddressed by central government. The new Article 63, which reads “El Salvador recognises Indigenous Peoples and will adopt policies for the purpose of maintaining and developing their ethnic and cultural identities, cosmovision, values, and spirituality,” is seen by many as the first step to repatriating indigenous people. Other efforts have included dual-lingual schools and publishing texts in native languages, although these efforts are largely without substance as very few elders now speak more than a passing fluency in these.

These people are seen as the invisible indigenous. Despite the fact they make up over 10 per cent of the population, the lack of shared customs, physical features and language has meant that many have been experiencing a crisis of identity. Often among the poorest in the country, those who prosper can sometimes be referred to as ladinos due to their economic status, meaning the community often remains in one social-economic status.

“Indeed, it may be argued that the Salvadorian Indians' collective identity as victims of injustice and crushing exploitation is the main ingredient that holds them together as an ethnic group.”(Source: Cultural Survival)

Written by ICS volunteers Katherine Maloney, Katherine Maynard and Benjamin White